Lunar samples from Apollo landings confirm a long-held theory

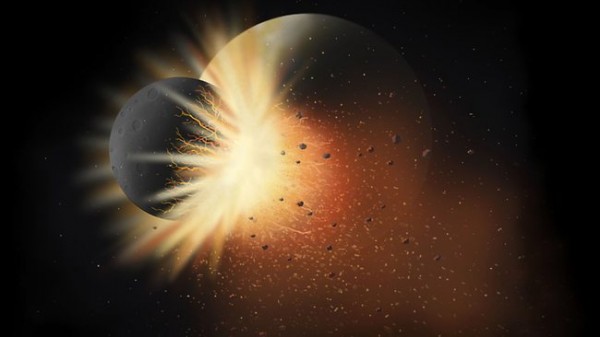

This illustration shows the collision between Earth and a smaller planet that formed the moon.

Newly analyzed lunar rocks have revealed the first direct evidence of the ancient smashup that created the moon, bolstering a long-held theory.

The rocks were gathered by astronauts on NASA’s Apollo missions. But newer scanning electron microscopes have now allowed scientists to detect in them the first chemical traces of the Mars-size planet thought to have blasted the proto-Earth around 4.5 billion years ago. (Related: “First Explorers on the Moon.”)

When the ancient planet, Theia, smashed into Earth, it blasted debris into space. The moon formed out of that debris. Planetary scientists first came up with this theory in the wake of the July 20, 1969, Apollo moon landing, offering an explanation for why our world has such a massive moon. (See: “It All Began in Chaos.”)

A team led by Daniel Herwartz of Germany’s Georg-August-Universität Göttingen reported the new findings about Theia on Thursday in the journal Science. (Related: “Moon 101.”)

“If the moon formed predominantly from the fragments of Theia, as predicted by most numerical models, the Earth and Moon should differ,” says the study.

Earlier looks at moon rocks hadn’t been detailed enough to reveal any difference in the lunar chemistry between them and rocks from the Earth. But this team found a small but significant difference—about 12 parts per million more of a heavier kind of oxygen atom in the moon rocks—that serves as a fingerprint of Theia.

Rogue Planet

The early solar system was a shooting gallery, Herwartz notes, with planets spun out of a disk of dusty material swirling around the young sun that occasionally smacked into each other.

“I think that Theia and the proto-Earth formed in the same region of the protoplanetary disk, more or less from the same material,” Herwartz says by email. He thinks roughly 30 to 50 percent of the moon might be Theia.

If Theia was particularly enriched with the heavier kind of oxygen atom, an isotope called oxygen-17, then it might make up less than 30 percent of the moon, he adds.

One outside alternative is that Theia and Earth were chemically identical, and that Earth was later hit by a comet or asteroid that carried a lot of water—proto-oceans—which rearranged Earth’s oxygen chemistry.

“This is possible, but unlikely,” Herwartz says. “If this was the case, however, the material that was added to the Earth (after the formation of the Moon) must have been very exotic,” he says. Meteorites with just such an exotic composition, he adds, must also have been rich in water.

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth