The apex predators, restored to the park in 1995, appear to be keeping the local population of plant-eating elk in check, which allows aspen saplings to grow tall and healthy

:focal(3111x1792:3112x1793)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9e/89/9e89a179-5480-4324-900c-dd78416ca9df/41b34fb4-aad5-4ec6-a58a-2b69b98c1ab8original.jpg)

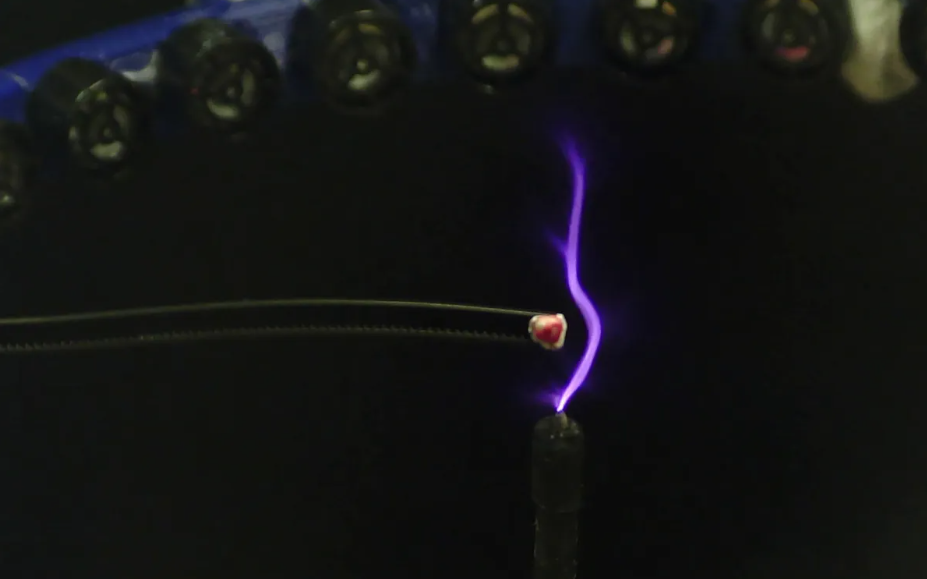

Aspen trees are getting a boost from wolves at Yellowstone National Park, new research suggests.

For the first time in 80 years, baby aspens are growing tall and healthy in the northern part of the park, scientists report in the journal Forest Ecology and Management. They’ve linked the trees’ resurgence with the reintroduction of gray wolves (Canis lupus), which are keeping Yellowstone’s plant-eating elk in check.

Gray wolves were once abundant in Yellowstone National Park. But by the 1930s, the apex predators had been extirpated from the area, largely due to hunting, government eradication programs and habitat loss.

Without the wolves, the park’s elk population ballooned, reaching around 17,000 individuals in winter 1995. The huge numbers of elk wreaked havoc on Yellowstone’s quaking aspen trees (Populus tremuloides) by chowing down on saplings before they had a chance to get established. When ecologists conducted surveys in the 1990s, they couldn’t find a single aspen sapling in the park.

“[The aspens] would grow new sprouts, but then the sprouts couldn’t get any larger [because of the elk],” says lead author Luke Painter, an ecologist at Oregon State University, to Oregon on the Record’s Michael Dunne. “The stands basically had older trees … and those were dying out, and then there wasn’t any new growth underneath, of young aspens, to replace those older trees.”

Then, in 1995, biologists reintroduced gray wolves to the park. The carnivores quickly made meals out of Yellowstone’s abundant elk, helping drive their population down to the roughly 2,000 individuals that spend winter in the park now. With fewer elk grazing, aspen saplings have been able to regain a foothold, the study authors suggest.

Scientists had previously surveyed 87 aspen stands in northern Yellowstone in 2012. When the new study’s team returned in 2020 and 2021, 43 percent of the sample sites had new, young trees with trunks that were at least two inches in diameter at chest height—something researchers hadn’t seen since the 1940s.

They also documented a more than 152-fold increase in the density of aspen saplings between 1998 and 2021.

“It doesn’t mean that they’re not going to get killed or die from something, but it’s a pretty good indication that we’re getting some new trees,” Painter says to Live Science’s Chris Simms. “As they get bigger, they get more resilient.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/29/78/297871bd-ef93-4073-bce3-6d9fa0bd6bb8/3d90402a-9d79-406a-8829-0407ae8b499doriginal.jpg)

The recovery of aspens in Yellowstone will likely benefit other species, too, including birds such as woodpeckers and tree swallows, which make cavity nests in aspen trunks. It will probably also be a boon to beavers, which eat the trees’ bark and small branches and use larger sections for their dams.Scientists say their findings are evidence of a “trophic cascade,” or a series of ripple effects caused by a change at the top of the food web.

“The reintroduction of large carnivores has initiated a recovery process that had been shut down for decades,” says Painter in a statement. “This is a remarkable case of ecological restoration… Wolf reintroduction is yielding long-term ecological changes contributing to increased biodiversity and habitat diversity.”

However, not all scientists are convinced that a trophic cascade has taken place at Yellowstone—yet. A 2024 study, for instance, found that Yellowstone’s ecosystems are still bouncing back from the previous loss of wolves. Researchers have also argued that reintroduced wolves were only one factor that affected elk numbers—humans and grizzly bears killed the herbivores, too. Meanwhile, even as elk have decreased, bison have flourished, adding a different pressure to the park’s vegetation.

“When you disturb ecosystems by changing the makeup of a food web, it can lead to lasting changes that are not quickly fixed,” said Tom Hobbs, the lead author of the 2024 study and an ecologist at Colorado State University, in a statement last year. “We can’t rule out the possibility that the ecosystem will be restored over the next 40 years as a result of the return of apex predators. All we can be sure of is what’s observable now—the ecosystem has not responded dramatically to the restored food web.”

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth